WRITTEN BY: Corey Nelson

Article at a Glance

Linoleic acid is an essential omega-6 fatty acid that’s required in small amounts (1-2% of total calories).

The average person today eats 6-10% or more of their calories from linoleic acid due to increasing consumption of vegetable oils made from seed crops.

Excessive linoleic acid intake is associated with inflammation, obesity, heart disease, and more.

Fortunately, it’s possible to reduce your stored tissue linoleic acid levels. The single most important change is to avoid seed oils and processed and prepared foods with high linoleic acid levels.

Other practices like exercise and intermittent fasting likely speed up linoleic acid depletion, but only if you eat a low linoleic acid diet.

Introduction

Linoleic acid might sound like an obscure or highly technical topic, but it shouldn’t be. It makes up 6-10% of calories in modern diets, yet many people today are still unclear about its roles in health and disease [*,*].

In this in-depth guide, we’ll cover the relevant facts, history, and health effects of linoleic acid, provide a comprehensive list of foods high in this fatty acid, and offer practical, research-backed advice to lower your linoleic acid levels and recover from excessive intake.

What Is Linoleic Acid?

Linoleic acid is an omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) that occurs naturally in a wide variety of foods, but especially in many nuts, seeds, and seed oils [*].

As the main component of vegetable oils made from seed crops, linoleic acid is a significant source of calories in many processed foods. And like other fatty acids, it contributes to the "mouthfeel" or sensory properties of foods by carrying flavor compounds and altering textures [*].

Linoleic acid is liquid at room temperature, colorless or lightly straw-colored, and flavorless or slightly bitter [*,*,*]. It’s molecularly unstable and prone to oxidizing (breaking down) into byproducts during storage and heating, and the bitter taste increases when it becomes rancid [*,*].

As an omega-6 fatty acid, linoleic acid is one of two naturally occurring essential fatty acids (EFAs) humans must obtain through diet [*]. In other words, your body can’t produce it from other compounds in foods.

Another EFA, α-linolenic acid or alpha-linolenic acid, has a name that sounds similar but is actually an omega-3 fatty acid. Like linoleic acid, you must also obtain omega-3 fatty acids from your diet.

Another name for linoleic acid is C18:2 or C18:2n6 (omega-6) due to its chemical structure, which contains 18 carbon atoms and two double bonds.

It’s called a polyunsaturated fatty acid or PUFA because it contains more than one double bond. In contrast, monounsaturated fatty acids (commonly found in olive oil) have only one double bond.

The History and Discovery of Linoleic Acid

Linoleic acid was initially isolated from linseed oil in 1844 at the laboratory of Justus von Liebig, one of the founders of organic chemistry in Germany, by Swiss scientist Frédéric Sacc [*,*].

Until 1929, no one suspected that dietary fatty acids were essential for humans or other animals because scientists knew that fats could be synthesized (produced in the body) from carbohydrates in foods [*]. But that year, George Oswald Burr and Mildred Lawson Burr, scientists at the University of Minnesota, discovered through experiments with rats that linoleic acid is an essential nutrient.

In a paper published in the Journal of Biological Chemistry in 1929, the Burrs described an experiment in which rats were given a fat-free diet and developed symptoms that suggested a deficiency of a nutrient found in fats [*,*].

Through additional experimentation, George and Mildred Burr discovered that the missing nutrient was linoleic acid [*]. They published a second paper in 1930 that demonstrated linoleic acid is an essential fatty acid (also the first use of the term), meaning it’s required for proper growth and prevention of disease in rats.

Linoleic acid is also essential for humans, but this hypothesis took several more decades to prove conclusively. The first convincing evidence came in the 1950s, when other researchers noted skin abnormalities in infants fed a low-fat diet that resolved when linoleic acid was added [*].

And later, in the 1960s, patients consuming long-term parenteral (IV) nutrition devoid of linoleic acid developed skin rashes and other signs of essential fatty acid deficiency, which also reversed after the addition of linoleic acid [*].

Linoleic Acid and Your Health

Linoleic acid is an essential nutrient, but deficiencies are extremely rare. (In fact, overconsumption of linoleic acid is a much more common issue today.)

The only documented instances of linoleic acid deficiency occur in [*,*]:

Infants who are given formula that doesn’t contain essential fatty acids like linoleic acid

Seriously ill patients on parenteral (IV) nutrition

People who are starving or severely malnourished

The symptoms of deficiency include dermatitis (skin rash and irritation), alopecia (hair loss), visible lightening of the hair, poor wound healing, and an increased risk of infections [*]. In younger people, linoleic acid deficiency can stunt growth.

Why You Don’t Need to Worry About Linoleic Acid Deficiency

Researchers estimate that you need around 1-2% of your daily caloric intake from linoleic acid to prevent deficiency [*]. For an adult eating 2,000 calories per day, that's approximately 2-3 grams of linoleic acid per day, which you can easily obtain from:

A tablespoon-sized serving of dried sunflower kernels (over 3 grams of linoleic acid) [*]

A half-ounce serving of pecans (nearly 3 grams of linoleic acid) [*]

A half-ounce serving of dehulled sesame seeds (over 2.5 grams of linoleic acid) [*]

An ounce of raw cashews (2.2 grams of linoleic acid) [*]

A half-ounce serving of shelled pistachios (slightly under 2 grams of linoleic acid) [*]

Three and a half ounces of cooked corn kernels (about 1.5 grams of linoleic acid) [*]

A roasted chicken thigh weighing 3.5 ounces (a little under 1.5 grams of linoleic acid) [*]

Many other foods contain trace amounts of linoleic acid, which is another reason deficiency is so rare — even if you never intentionally eat linoleic acid, there’s virtually zero chance of developing a deficiency.

The Unprecedented Increase in Linoleic Acid Intake

Although low amounts of linoleic acid are essential to prevent deficiencies, the average person today eats around 6-10% of their overall calories from linoleic acid [*,*].

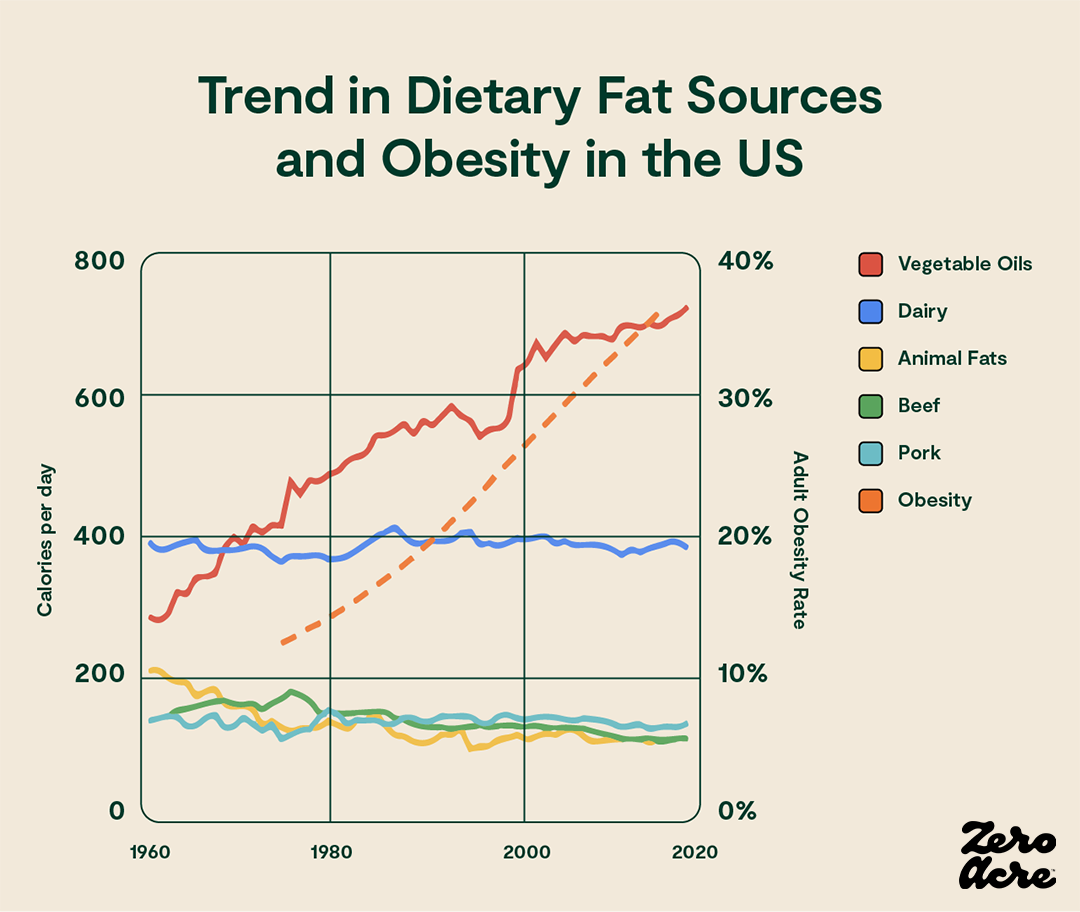

The main reason for this increase is because of the dramatic global rise in vegetable oil consumption, particularly soybean oil and sunflower oil [*]:

Before the 20th century, people obtained adequate linoleic acid levels from whole foods. But the introduction of vegetable oils and industrial seed oils resulted in much higher levels of linoleic acid intake.

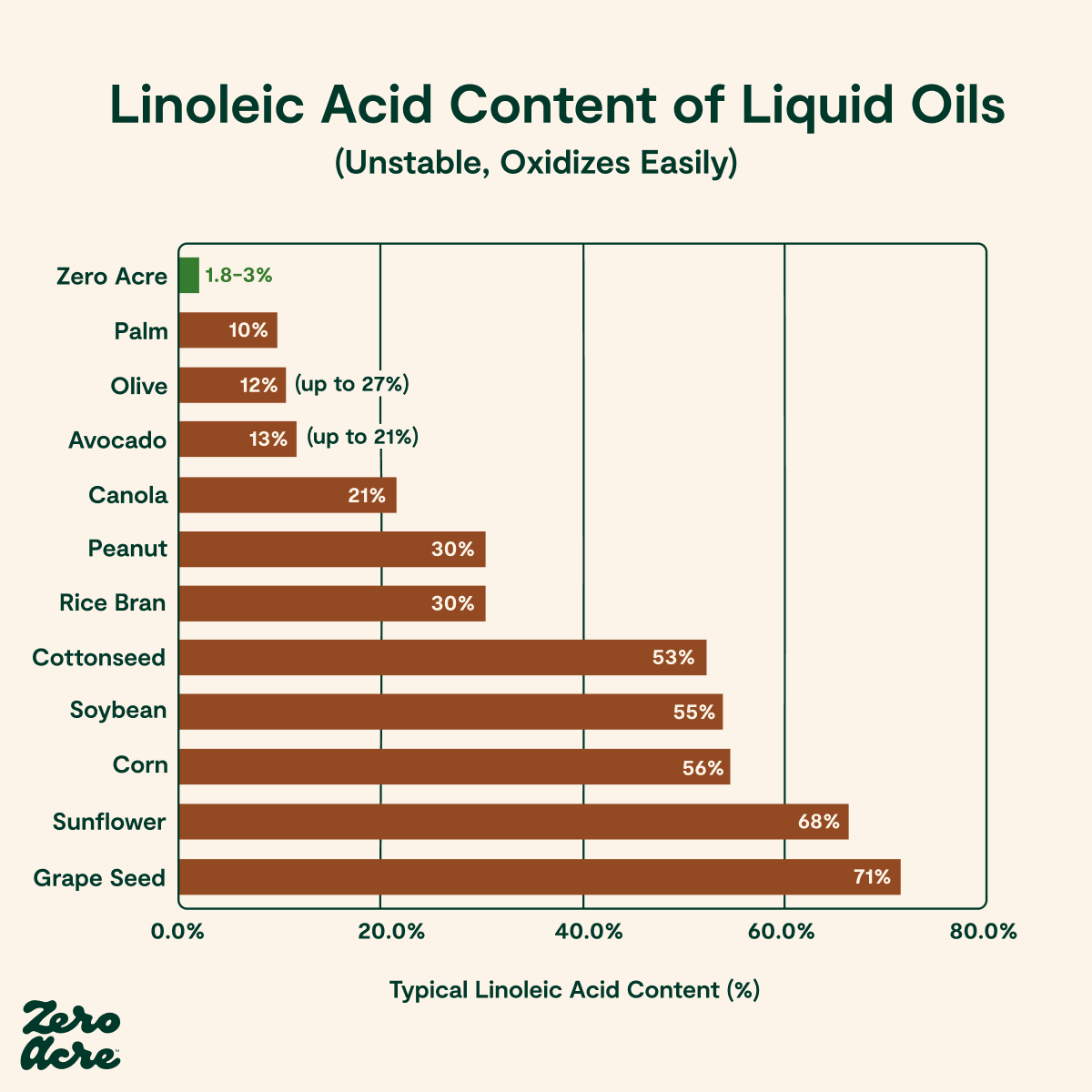

For example, soybean oil, commonly found in processed foods and used in restaurants, contains about 55% linoleic acid [*]. And since 1909, human consumption of these vegetable oils high in linoleic acid has increased from virtually zero to as much as 20% of overall calories [*].

Is Linoleic Acid Good or Bad?

Low amounts of 1-2% linoleic acid are necessary for survival, but research links higher intakes to health problems, including inflammation, heart disease, cancer, dementia and other neurological disorders, diabetes, and obesity [*,*,*,*].

And the average person today is eating far more linoleic acid than at any other time in history. Until the 20th century, most people didn’t consume vegetable oils or seed oils high in linoleic acid — they easily obtained the necessary amounts from nuts and grains, and trace amounts in other foods, including meat, eggs, and dairy.

According to a paper from the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, per capita consumption of soybean oil (which contains approximately 55% linoleic acid) increased 1000-fold from 1909 to 1999, along with increases in other industrial omega-6 seed oils that weren’t widely available before the 20th century [*].

As a direct result of eating more oils high in linoleic acid, most people are now consuming 6-10% or more of their calories from linoleic acid, and nutritional surveys suggest intakes will continue to increase [*,*,*].

So, why is this such a problem? Because it’s an omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acid, linoleic acid is inherently unstable. It oxidizes (breaks down) more readily than most other fats — this is true during manufacturing, storage, transportation, and cooking as well as in your body after you eat it [*,*,*,*,*].

And since your body incorporates it directly into cellular membranes, excess linoleic acid bioaccumulates (builds up) in cells over time, resulting in instability and inflammation at the cellular level [*,*,*].

Finally, overconsuming linoleic acid also creates an imbalance between omega-6 and omega-3 fats in your body and depletes anti-inflammatory omega-3s in tissues [*].

Researchers think that humans naturally evolved to consume an equal ratio of these fats, but many people today now consume 20 times higher levels of omega-6 than omega-3 fats [*].

Eating too much linoleic acid disrupts healthy cellular function and contributes to inflammation [*,*]. Over-consuming inflammatory omega-6 linoleic acid can also reduce tissue levels of anti-inflammatory omega-3s, causing more inflammation and exacerbating this imbalance [*].

Next, we’ll examine peer-reviewed studies that explore the health effects of consuming too much linoleic acid to understand how this fatty acid affects your health over time.

Linoleic Acid and Heart Health

When you consume a diet high in linoleic acid, it results in higher levels of linoleic acid in cells and tissues, including [*]:

Erythrocytes (red blood cells)

Thrombocytes (platelets)

Cholesterol

The endothelium (blood vessel linings)

These changes are linked to an increased risk of atherosclerosis and other types of fatal cardiovascular disease [*].

But what about the claim that high-linoleic vegetable and seed oils are supposed to be good for your heart?

The idea that linoleic acid in vegetable oils was “heart-healthy” originally came from experiments conducted in the 1950s-1970s.

But recently, United States National Institutes of Health (NIH) researcher Christopher Ramsden used modern statistical analysis and recovered data from the same experiments, which included nearly 11,000 participants, to re-evaluate the original findings on linoleic acid.

After reviewing the results of the Rose Corn Oil Trial, the Sydney Diet Heart Study, the Minnesota Coronary Experiment, and the LA Veterans heart health study, the Ramsden group found no benefit and consistent evidence of harm from increasing dietary intake of linoleic acid [*,*,*].

Importantly, each of these studies initially sought to demonstrate the benefits of linoleic acid consumption, yet their results did the opposite. And despite not being recent, they’re the only randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of their kind that investigated the effects of increasing linoleic acid on heart disease risk and all-cause mortality (death).

More recent large-scale studies on the effects of linoleic acid use observational or epidemiological methods to determine population-wide results through correlation, but without any randomization.

As a result, their findings are mixed (some showing evidence of harm, others of benefit), which may be due to the “healthy observer” effect [*].

In other words, because public health officials touted omega-6 vegetable oils as healthy for decades, people who generally listen to public health advice about tobacco, alcohol, and trans fats are also more likely to consume high-linoleic-acid diets. This skews observational data in a way that doesn’t occur in well-designed RCTs and reduces the reliability of newer, non-RCT findings [*].

However, a plethora of experimental evidence illuminates the reasons for Ramsden’s findings.

Linoleic Acid and Cardiovascular Disease: Summary of Experimental Evidence

Linoleic acid is less stable than other fatty acids and is more prone to oxidation (breakdown).

In other words, when linoleic acid gets incorporated into LDL (low-density lipoprotein, a type of cholesterol), this process results in increased formation of oxidized LDL molecules in the circulatory system [*]. And oxidized LDL cholesterol is directly linked with inflammation and the formation of arterial plaques [*].

Here’s a summary of other research findings that show the implications of a high linoleic acid diet for heart health [*]:

Linoleic acid levels in adipose (fatty) tissues and blood platelets positively correlate with cardiovascular disease.

Patients with cardiovascular disease have higher concentrations of linoleic acid in their plasma than the general population.

Compared to healthy patients, increased levels of linoleic acid oxidation products occur in the LDL and plasma of patients with atherosclerosis (hardening of the arteries).

Higher amounts of linoleic acid oxidation byproducts have been found in arterial plaques, and the degree of oxidation correlates directly with the severity of atherosclerosis.

Linoleic acid is the most abundant fat occurring in arterial plaques.

Linoleic acid and its byproducts have been demonstrated to induce direct toxic effects on the endothelium (blood vessel lining).

Ultrasound studies of healthy patients with high levels of 9-HODE (a linoleic acid oxidation byproduct) in carotid arteries also show signs of atherosclerosis.

Individuals who die from sudden cardiac death tend to have more linoleic acid in their coronary arteries versus controls.

A meta-analysis by Ramsden, et al. of randomized controlled trials in humans found that substituting omega-6 linoleic acid in place of saturated fat and trans-fats increases all-cause mortality as well as deaths from heart disease [*].

Dietary changes that increase monounsaturated fat or decrease omega-6 linoleic acid are shown to decrease the likelihood of LDL oxidizing.

*References

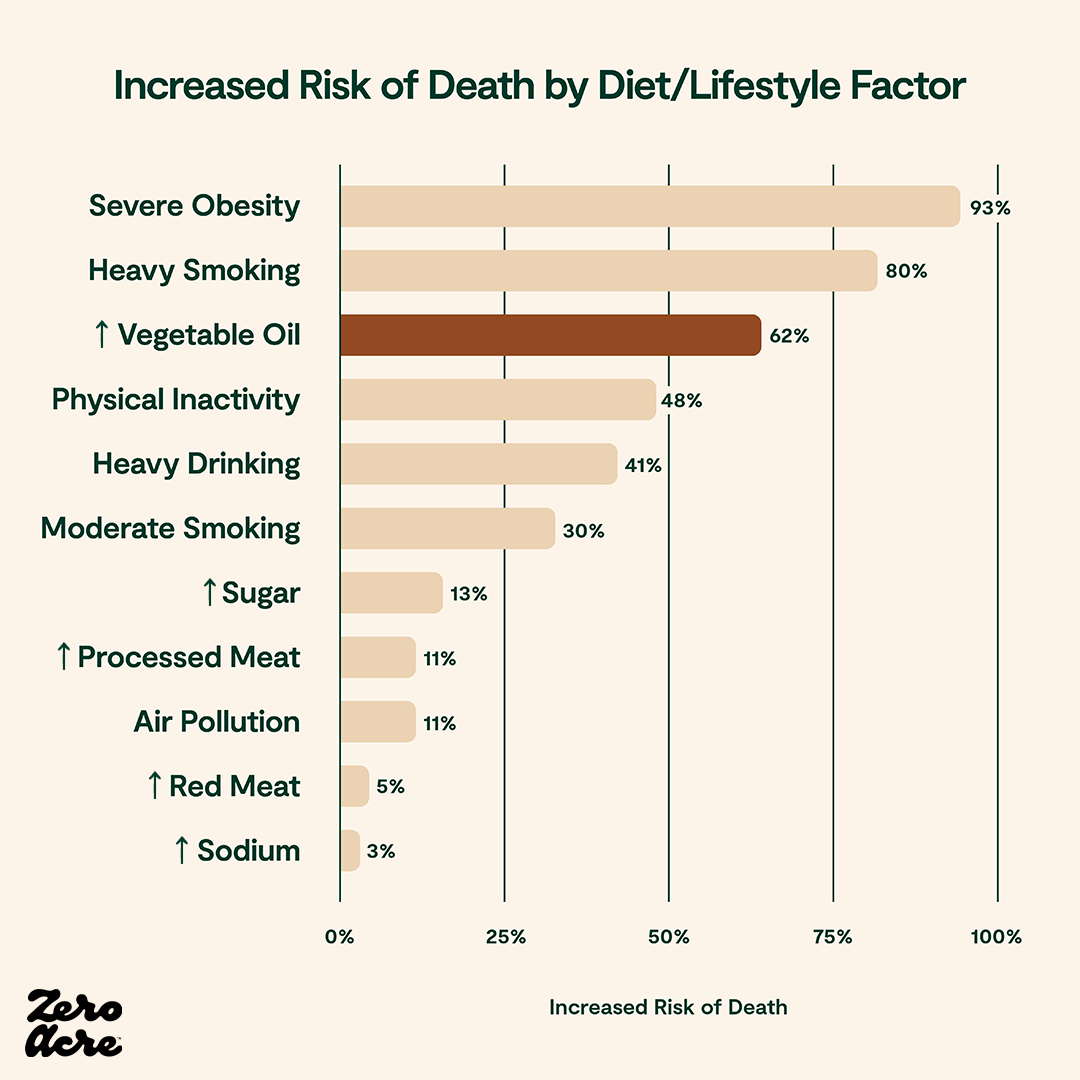

In the Ramsden group’s re-evaluation of the Sydney Diet Heart Study clinical trial, high omega-6 linoleic acid intake from vegetable oils resulted in a 62% increased risk of death from all causes.

Linoleic Acid and Cancer

While there’s currently no direct evidence that linoleic acid is carcinogenic (causing cancer in and of itself), compelling experimental evidence shows that linoleic acid may promote or contribute to tumor growth [*]. In fact, some research suggests that linoleic acid is required for the development of mammary (breast) tumors in mice [*].

In vitro (cell studies) and studies of linoleic acid consumption in animals have found [*]:

Seed oils high in linoleic acid promote mammary (breast) cancer in rats.

Mixed results (beneficial as well as harmful) affecting the severity of colon cancer in rats exposed to carcinogens.

Linoleic acid increases tumor growth in cell studies of experimental tumors.

A possible role of linoleic acid in the growth of breast, colon, and prostate tumors in humans and animals.

Linoleic acid may increase the growth of some tumors because, like other cells, some types of cancer may rely upon this fatty acid to construct cell membranes [*].

For that reason, according to a 2017 peer-reviewed paper in the journal Healthcare, reducing linoleic acid intake combined with conventional cancer therapies may be a low-risk yet beneficial intervention for cancer patients [*].

Another way linoleic acid may contribute to cancer formation or growth is by increasing cellular inflammation, which “predisposes to the development of cancer and promotes all stages of tumorigenesis” (tumor formation and growth) [*].

According to population-wide observational data, the increasing incidence of breast cancer, prostate cancer, melanoma, lung cancer, and bladder cancer in humans beginning in the middle of the 20th century mirrors increasing intakes of linoleic acid [*].

And in the case of rising melanoma rates, several cancer researchers have concluded that increasing linoleic acid intakes better explain this phenomenon than increases in sun exposure over the same period [*,*,*,*].

According to results from the 1960s Los Angeles Veterans study conducted by the American Heart Association, a trial including over 800 veterans, the men receiving diets high in linoleic acid (15% of daily calories from linoleic acid versus 4% in the control group) were 82% more likely to die of cancer [*].

Another way that linoleic acid may increase the risk of cancer is through cooking fumes.

When oils are heated during cooking, and especially overheated or heated to their smoke points, they not only produce harmful byproducts in foods, but also release dangerous fumes.

For example, in one meta-analysis of over 9,500 Chinese women who didn’t smoke, researchers found that increased exposure to cooking oil fumes could potentially increase the risk of lung cancer by more than double [*].

Any overheated oil can create harmful fumes, regardless of its linoleic acid content. However, omega-6 fatty acids like linoleic acid appear to result in significantly higher levels of dangerous polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and aldehydes during high-temperature cooking compared to other cooking oils [*,*,*].

The best ways to lower your exposure to carcinogenic cooking oil fumes are to ensure your kitchen has adequate ventilation and to cook with oils low in linoleic acid and other unstable polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs).

Linoleic Acid and Brain Health

While minimal amounts of dietary linoleic acid are essential for cells, higher levels may increase brain inflammation [*]. Linoleic acid enters the brain, where it's primarily used for fuel, producing oxidized metabolites and other harmful compounds that can damage the brain [*,*].

According to the author of a 2020 paper published in Nature's Science of Food peer-reviewed journal, current evidence suggests that consuming a diet low in linoleic acid may be neuroprotective (beneficial for preserving brain and nervous system functioning) [*].

Evidence from systematic reviews of studies suggests that a high omega-6-to-omega-3 ratio increases the chances of Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia [*]. And because diets high in linoleic acid can deplete omega-3 from tissues, reducing your omega-6 intake is the best way to maintain a healthy ratio of essential fatty acids [*].

In the Zutphen Elderly Study, conducted in the Netherlands on 476 adults aged 70-89, high linoleic acid intake increased the odds of cognitive impairment or dementia by 80% [*].

According to animal evidence, high dietary linoleic acid intake increases the production of compounds involved in pain signaling, which suggests that linoleic acid may be partially responsible for some types of chronic idiopathic pain (chronic pain with unknown causes) [*].

A randomized controlled trial of women with migraine headaches found that reducing omega-6 linoleic acid intake and increasing omega-3 fatty acid intake changed biomarkers of headaches and decreased the frequency and severity of headaches, suggesting that high linoleic acid levels likely play a role in chronic migraines [*].

Linoleic Acid, Obesity, and Diabetes

Next, we’ll review the available evidence linking high linoleic acid diets to obesity, diabetes, and related metabolic disorders.

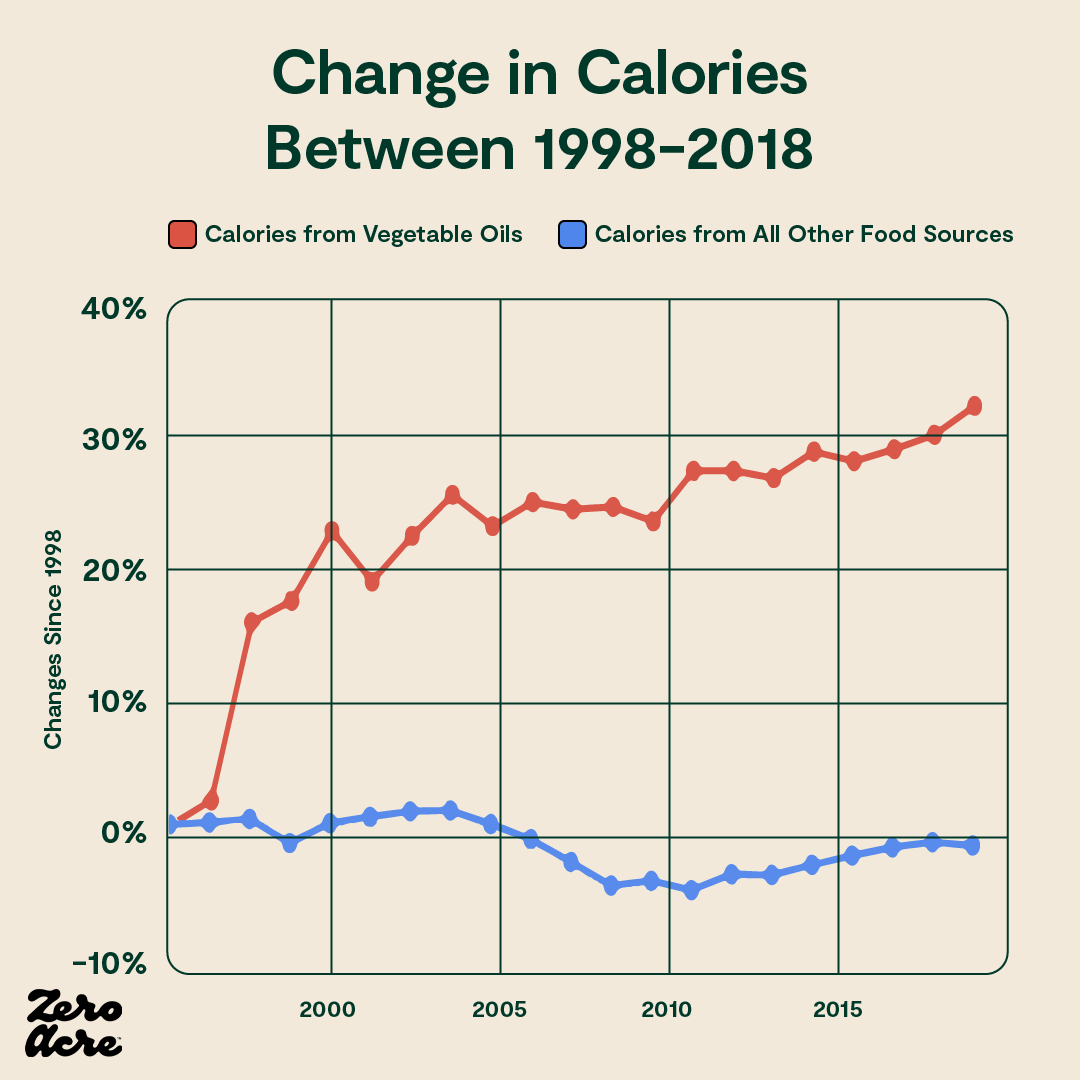

The rate of obesity in the United States is increasing, but surprisingly, data from the last 20 years shows that Americans are eating the same or fewer calories and exercising more on average [*,*,*,*,*].

However, while caloric intake has stayed relatively flat, vegetable oil consumption is way up — and as a result, so is linoleic acid intake.

A similar trend is occurring in Japan, where average caloric intake remained constant from 1975-2013, yet obesity rates increased four-fold — and during the same time, consumption of vegetable oils high in omega-6 linoleic acid doubled [*,*].

Of course, population-wide correlations between linoleic acid intake and obesity don’t prove, all by themselves, that linoleic acid is the main culprit in these trends. But these data sets, at the very least, demonstrate that calorie intake and exercise aren’t the only causes of rising obesity as is commonly assumed — and raises the question of what else could be the cause.

Line graph showing the degree to which particular sources of dietary fat contributed to our daily calorie total (left Y-axis) over the years (bottom X-axis) as the adult obesity rate increased (right Y-axis).

Here’s a summary of experimental and observational data that lends credence to the hypothesis that linoleic acid may be driving obesity trends in the United States and other industrialized countries:

Studies in yeast and roundworms show that 4HNE (4-Hydroxynonenal), an aldehyde byproduct of linoleic acid, dramatically increases cellular fat accumulation [*,*].

In a mouse study where researchers inserted a human genetic mutation that decreases clearance of the 4HNE aldehyde, the mutant mice accumulated more fat and gained more weight than control mice, despite eating the same diet and engaging in the same levels of activity [*].

Other studies show similar results of 4HNE levels correlating with obesity in animals and people [*,*,*,*].

Fried foods high in linoleic acid also contain high levels of 4HNE [*].

Even with similar calorie consumption, people who eat more fried foods high in linoleic acid and 4HNE are 26% more likely to be obese than people who eat minimal amounts [*].

High intakes of linoleic acid and other omega-6 fats in humans appear to increase inflammation and endocannabinoid levels, which some researchers assert disrupts body weight regulation by altering fat storage and increasing appetite [*,*].

One intriguing reason for some of these changes could be that omega-6 linoleic acid intake appears to serve as a hibernation signal for many mammals [*].

In other words, evidence from the field of evolutionary biology suggests that in many animals, during autumn, eating foods naturally high in linoleic acid acts as a signal that increases fat accumulation and decreases metabolism, helping them go up to six months without food.

While humans don’t hibernate, we do actually share many metabolic genes with mammals that do [*]. That’s a potential reason that unnaturally high linoleic acid levels could reduce your metabolism and increase fat storage, even if you’re not eating more calories day-to-day.

Another possible outcome of linoleic acid intake, insulin resistance, is associated with obesity as well as type 2 diabetes and other metabolic disorders [*]. Insulin resistance occurs when some cells become less responsive to the energy storage hormone insulin, resulting in higher blood sugar levels and strain on your pancreas (the organ that produces and releases insulin).

Although findings on linoleic acid and type 2 diabetes are mixed, there is evidence suggesting that excessive omega-6 intake contributes to diabetes and related problems:

High levels of omega-6 linoleic acid and low levels of omega-3 fatty acids in muscle tissue correlate to insulin resistance in muscle tissues [*].

A 2-week study of 11 men with controlled type 2 diabetes found that high linoleic acid intakes resulted in higher fasting blood glucose and insulin levels [*].

In a mixed study of 27 coronary artery surgery patients and 13 healthy participants, fasting serum insulin concentrations correlated with linoleic acid as a percentage of fatty acids in surgical patients [*].

Lastly, an in vitro study of retinal cells and other, related cells of the eye found that linoleic acid stimulated the production of inflammatory compounds involved in diabetic retinopathy (disease of the retina), which did not occur in the presence of glucose alone [*].

Linoleic Acid and Eye Health

Because the eye is high in polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), your linoleic acid intake can negatively affect your eye health [*]. Research studies suggest a direct link between linoleic acid intake and eye disorders, including macular degeneration, glaucoma, and cataracts.

The human retina, the innermost layer of the eye, is the most metabolically "expensive" organ, meaning it consumes oxygen more rapidly than any other tissue in the body [*]. The high metabolism and blood flow also mean that it’s highly sensitive to oxidative stress (cellular damage from free radicals).

Macular degeneration happens when the macula, the layer of your retina responsible for central vision (seeing what’s in front of you) and most color perception and detail, becomes damaged [*]. It’s the most common cause of blindness in developed countries and is especially common after age 60.

In a study published in JAMA Ophthalmology, researchers assessed 349 individuals with advanced, age-related macular degeneration (AMD), aged 55-80, according to their fat intake while controlling for cigarette smoking and other known risk factors [*]. In the analysis, they also included 504 controls without AMD, but who had other ocular diseases, to learn about the relative risk of AMD.

The study found [*]:

An elevated risk of AMD with high vegetable fat consumption: over a two-fold increase in risk for high versus low vegetable fat intake.

Reduced risk of AMD with a higher frequency of fish intake or other omega-3 sources, but only when the diet was low in linoleic acid.

No benefit of omega-3 fatty acids or fish intake among people with high levels of linoleic acid intake. (This finding shows that additional omega-3s aren’t enough to reverse the effects of linoleic acid without also reducing omega-6 consumption.)

The study also found increased AMD risk at the highest intake levels of monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats. However, the risk increase wasn’t as great compared to high intakes of vegetable oils or linoleic acid, and they didn’t control for intake of trans fats. In other words, the people with the highest levels of fat consumption in general would likely be eating more trans fats, which are also a risk factor for macular degeneration [*,*].

Another separate study that did control for trans fat intake found that while high trans fat intake raised the risk of AMD by 76%, eating at least 8.5 teaspoons per week of olive oil (high in monounsaturated fat) actually lowered the risk by slightly over half [*]. These results show that monounsaturated fat wasn’t the culprit in the original study on linoleic acid and other fats.

A 2019 study found that levels of hydroxylinoleate (abbreviated HODE), a toxic byproduct of linoleic acid, were higher in patients with open-angle glaucoma, the most common form of glaucoma [*].

Glaucoma is an eye disorder that can cause vision loss and blindness due to a lack of drainage of liquids from the eye. In glaucoma, the build-up of fluids increases pressure in the eye, resulting in irritation, pain, and damage to the optic nerve [*].

In the study, people with glaucoma had higher levels of harmful HODE linoleic acid byproducts compared to controls, and patients with high intraocular pressure (associated with the progression and severity of glaucoma) had higher HODE levels compared to glaucoma patients with normal pressure [*].

The study didn’t assess glaucoma symptoms according to linoleic acid levels, but other human research shows that lowering your linoleic acid intake can significantly reduce your circulating HODE levels in 12 weeks or less [*].

As with other eye diseases, fatty acids also appear to play a role in cataracts. Cataracts occur when proteins and fibers in the cornea (the natural lens of the eye) become damaged and break down, causing a “cloudy” appearance and visual impairment [*].

In the Nurses’ Health Study, a study of 71,083 women followed for 16 years, higher levels of linoleic acid intake (up to an average of 6.3% of calories, which is below today's average intake) correlated with a 7-11% higher risk of any cataract surgery [*]. Because the study didn’t include diagnoses of cataracts where surgery wasn’t performed, the actual increased risk of cataracts may have been even higher.

Linoleic Acid and Fertility, Pregnancy, and Child Development

Because linoleic acid accumulates in gametes (egg and sperm cells), it may reduce fertility and interfere with healthy child development according to studies in humans, animals, and cells.

A 2020 study of fetal development in rats found when given high linoleic acid diets (6.21%, comparable to or lower than the average human intake today) for 10 weeks before pregnancy and during gestation, their placenta had increased linoleic acid levels, decreased levels of omega-3 fatty acids, and increased expression of inflammatory proteins compared to rats receiving a low linoleic acid diet (1.44% LA). [*].

And a 2010 in vitro (cell) study examining the effects of linoleic acid supplementation on bovine oocytes (immature egg cells from cows) found that the omega-6 fat interfered with the maturation of the egg cells and inhibited the development of embryos [*]. And in 2016, a separate research group conducted a study using similar methods and found the same results [*].

In a 2018 Korean study of 1407 pregnant women, high maternal intake of omega-6 fatty acids was significantly linked with a nearly 2.5-fold risk of infants being below the 10th percentile of birth weight as well as 57% lower odds of having a child above the 90th percentile of birth length [*]

Another study of 12,373 women from the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition in 2008 found that women with high concentrations of omega-6 fats in their plasma were significantly more likely to have babies with a low birth weight and fetuses that were small for their gestational age [*]. According to the study’s findings, on average, infants born to the 7% of women with the most unfavorable fatty acid profiles of omega-6 and omega-3 were 125 grams lighter and twice as likely to be small for their gestational ages.

Additionally, a 2012 paper on aging, animal and human data suggests that diets high in linoleic acid and other omega-6 fats may make having children difficult for older women [*].

Some human studies of in vitro fertilization (IVF) have found increased fertility rates with higher linoleic acid levels, but these studies didn’t control for omega-3 intake, which makes the results inconclusive [*,*].

A small study of 200 women found no correlation between difficulty conceiving or miscarriage with serum levels of omega-6, omega-3, or their ratio [*]. A larger study would provide better insight into this issue.

In a 2010 study comparing the seminal plasma of fertile and infertile men, men who were unable to conceive children had significantly higher levels of linoleic acid, and lower ratios of omega-6 to omega-3, than men who had successfully conceived [*].

A separate study conducted in 2006 also found that in men who had difficulty conceiving, the sperm fatty acid omega-6-to-omega-3 ratio was higher compared to fertile men [*].

Research findings examining the relationship between linoleic acid levels during pregnancy or breastfeeding and later outcomes in developing children include:

Mothers eating prenatal diets high in linoleic acid resulted in a two-fold increase in the risk of delayed psychomotor and mental development in 6-month-old infants [*].

A significant association was found between mid-pregnancy plasma linoleic acid levels and the risk of autistic traits in 6-year-old children [*].

Higher ratios of omega-6 to omega-3 fats during pregnancy were associated with an increased risk of allergic rhinitis in children by age 5 [*].

Colostrum levels of linoleic acid (LA) were associated with reduced motor and cognitive scores [*]. Children breastfed with the highest levels of linoleic acid scored closer to never-breastfed children than to children fed breast milk low in linoleic acid.

High maternal breast milk linoleic acid percent composition (greater than 9.7% of fatty acids) was associated with reduced motor and cognitive scores in 2- to 3-year-olds as well as reduced verbal IQ at ages 5-6 [*].

An association between high levels of linoleic acid in breast milk and low cognitive scores was shown in 15-year-old children, suggesting a lasting impact on development [*].

A fatty acid analysis of human milk samples from 28 countries showed a correlation between high linoleic acid levels and low test scores in math, reading, and science, even when controlling for socioeconomic factors like wealth and parental education [*].

When mothers eat diets high in linoleic acid, the linoleic acid accumulates in their breast milk [*,*].

Between 1970 and 2000, the average linoleic acid levels in breast milk increased by 71%, from 7% initially up to 12% of total fatty acids, or 8% of total energy, which is at least four times higher than required to prevent deficiencies in children [*].

Unfortunately, infant formula is also high in linoleic acid from vegetable oils like soybean oil [*]. And many brands have a high ratio of omega-6 linoleic acid to omega-3 alpha-linolenic acid, which lowers tissue levels of omega-3s and reduces visual functioning in infants [*,*,*].

Several scientists have recently proposed lowering the maximum allowed levels of linoleic acid in infant formula, or primarily substituting healthy monounsaturated fats in place of linoleic acid in formula, to improve child development outcomes [*,*].

Linoleic Acid and Inflammatory Disorders

As we’ve already covered in this article, linoleic acid is involved in the production of inflammatory signaling compounds in your body [*]. It also breaks down into toxic, inflammatory byproducts and reduces tissue levels of anti-inflammatory omega-3 fatty acids [*,*].

With these observations in mind, it makes sense that excess linoleic acid consumption is involved in an array of inflammatory disorders.

In a study of 203,193 European men and women aged 30-74, the highest levels of linoleic acid intake increased the risk of developing ulcerative colitis by 2.5-fold [*]. This trend held across varying linoleic acid intake levels.

And in a study of patients with the similar condition, Crohn's disease, omega-6 linoleic acid stimulated a 9-times-greater increase in interleukin-8, an inflammatory compound, compared to baseline, while monounsaturated fat did not [*]. The researchers concluded that replacing linoleic acid with healthy monounsaturated fats might decrease inflammatory activity in Crohn’s.

In a study of patients with irritable bowel disease (IBD), an umbrella disorder that includes ulcerative colitis and Crohn's, the IBD patients had higher linoleic acid levels in their red blood cell membranes [*].

Other human research implicates high linoleic acid levels in rheumatoid arthritis, asthma, chronic pain, and migraine headaches [*,*,*].

Which Foods are High in Linoleic Acid?

The foods highest in omega-6 linoleic acid are pre-packaged or prepared foods with added vegetable oils from seed crops. Because industrial seed oils are much higher in linoleic acid than naturally occurring whole foods, the intake of these oils is the main source of linoleic acid in modern diets [*].

To reduce your linoleic acid intake, the first step is to watch for these oils and avoid eating foods that list them as ingredients on the label:

Safflower oil (71% linoleic acid) [*]

Grapeseed oil (71% linoleic acid) [*]

Sunflower oil (66% linoleic acid) [*]

Corn oil (60% linoleic acid) [*]

Soybean oil (55% linoleic acid) [*]

Cottonseed oil (53% linoleic acid) [*]

Rice bran oil (30% linoleic acid) [*]

Canola (rapeseed) oil (21% linoleic acid) [*]

And because nearly all restaurants use these high linoleic acid oils for sauteing and frying foods and as ingredients in dressings, sauces, marinades, and baked goods, the best way to reduce your intake is to cook at home whenever possible or ask your server about the fats used to prepare your meals.

Also, be aware that instead of 100% extra virgin olive oil, most restaurants use a blend of olive oil and canola, soybean, grapeseed, or safflower oil to reduce the cost and make it taste milder.

Low-quality olive oil products are more likely to be adulterated with high linoleic acid oils, even when they aren’t labeled as such — journalists have reported that 80% of imported olive oil is adulterated and/or mislabeled [*].

Another way to avoid high linoleic acid cooking oils at restaurants is to order seared or grilled meat or seafood with vegetables and no added oils at all.

Using Zero Acre oil or other vegetable oil substitutes when you cook at home will also reduce your linoleic acid intake.

Linoleic Acid Content of Pre-packaged Foods

Some of the biggest sources of high linoleic acid vegetable oils in people’s diets are pre-packaged, fat-based products like mayonnaise and salad dressing [*].

Here’s how much linoleic acid common brands contain, on average, according to survey data from the USDA:

Caesar salad dressing is 29% LA by weight, 48% LA by calories, and contains 8.5 grams of LA per two-tablespoon serving [*].

Blue cheese (bleu cheese) or roquefort dressing or dip is 24% LA by weight, 45% LA by calories, and contains 7.4 grams of linoleic acid per serving [*].

Soy ginger dressing is 23% LA by weight, 47% LA by calories, and contains 6.8 grams of linoleic acid per two-tablespoon serving [*].

Ranch dressing and similar creamy dressings (like Italian dressing) are 22% linoleic acid by weight, 47% LA by calories, and contain 6.6 grams of linoleic acid per two-tablespoon serving [*].

French or Catalina dressing is 20% LA by weight, 43% LA by calories, and contains 6.2 grams of linoleic acid per two-tablespoon serving [*].

Green goddess avocado dressing is 20% LA by weight, 43% LA by calories, and contains 6.2 grams of linoleic acid per two-tablespoon serving [*].

Honey mustard dressing is 20% LA by weight, 39% LA by calories, and contains 6.3 grams of LA per two-tablespoon serving [*].

Thousand island dressing is 16% LA by weight, 38% LA by calories, and contains 5 grams of LA per two-tablespoon serving [*].

Russian dressing is 13% LA by weight, 33% LA by calories, and contains 4 grams of linoleic acid per two-tablespoon serving [*].

Italian dressing with oil and vinegar is 9.2% LA by weight, 35% LA by calories, and contains 2.7 grams of linoleic acid per two-tablespoon serving [*].

Mayonnaise is 39% LA by weight, 59% LA by calories, and contains 5.4 grams of linoleic acid per tablespoon serving [*]

Sandwich spread is 18% LA by weight, 42% LA by calories, and contains 2.7 grams of linoleic acid per tablespoon serving [*].

Reduced-fat mayonnaise with olive oil is 3.7% LA by weight, 10% LA by calories, and contains half a gram of LA per tablespoon serving [*].

Vegan mayonnaise is 9% LA by weight, 35% LA by calories, and contains 1.3 grams of LA per tablespoon serving [*].

Savory or sweet snacks, candy, and other ultra-processed, packaged foods are also a major source of linoleic acid from seed oils:

Cheese-flavored snack crackers (per 56 g serving): 5.2 grams of LA [*]

Cheese puffs (per 28 g serving): 4.9 grams of LA [*]

Onion dip (per 30 g serving): 4.6 grams of LA [*]

Tortilla chips (per 30 g serving): 3.2 grams of LA [*]

Potato chips (per 28 g serving): 2.2 grams of LA [*]

Whole wheat crackers (per 30 g serving, 16 crackers): 2 grams of LA [*]

Butter-flavored snack crackers (per 16 g serving, 5 crackers): 1.5 grams of LA [*]

Glazed donut (per small 75 g donut): 3.2 grams of LA [*]

Peanut butter cups (per 44 g two cup serving): 2.5 grams of LA [*]

Vanilla ice cream (per medium 240 g ice cream cup): 0.7 grams of LA [*]

Milk chocolate candy bar (per 44 g bar): 0.5 grams of LA [*]

Chocolate chip cookies: (per large 45 g cookie): 3.4 grams of LA [*]

Vanilla wafer cookies (per 30 g serving): 1.8 grams of LA [*]

Breakfast toaster tart pastries (per 54 g tart): 1.6 grams of LA [*]

Frozen microwave dinner (fried chicken, potatoes, vegetable, and dessert, 468 g total serving size): 8.8 grams of LA [*]

Frozen mixed berry pie (one 173 g slice): 3.8 grams of LA [*]

Depending on the food, even a small portion can leave you consuming too much linoleic acid for the day.

The easiest way to avoid high linoleic acid products is to carefully read nutrition labels and avoid items containing soybean oil, sunflower oil, corn oil, and other vegetable oils made from seed crops.

Linoleic Acid in Meat, Eggs, and Seafood

The linoleic acid levels in animal products like meat, eggs, and seafood vary because of several factors.

In most animal species, as in humans, dietary linoleic acid from feed increases tissue linoleic acid levels significantly [*,*,*]. But this isn’t the case in cows and other ruminants (grazing animals with multiple stomachs) [*].

The meat and eggs of non-ruminants (including fish) fed inexpensive agricultural feed with high linoleic acid, such as corn and soy, contain high levels of linoleic acid.

However, when it comes to meats like beef, bison, elk, deer, or milk from cows or goats, linoleic acid levels stay relatively low regardless of feeding.

Because of this, beef is a widely available meat option with low linoleic acid levels, even if it’s fed corn and soy instead of pastured or grass-fed.

But the same isn’t true of other common meats like chicken or pork, or eggs of any type. And even if they are labeled “pastured,” these are often supplemented or “finished” with grains high in linoleic acid to add weight quickly, which raises their linoleic acid content.

To keep your linoleic intake as low as possible, you’ll need to choose corn-free, soy-free animal products (aside from ruminant products like beef and dairy).

Similarly, with seafood, the highest levels of linoleic acid occur in farm-raised fish because they’re also fed high linoleic acid diets. Wild-caught fish and shellfish are low in linoleic acid because they eat natural, species-appropriate diets.

Here are the specific levels of linoleic acid (LA) in common meats as percentages of total fatty acids:

Grass-fed cattle: 2% LA [*]

Grain-fed cattle: 2.4% LA [*]

Foraging pork: 2% LA [*]

Industrially farmed pork: 18.5-21% LA [*]

Foraging chicken and other fowl (estimated): 2.5% LA [*]

Pastured chicken or fowl consuming 50% of calories from cereal-based feed: 20.6% LA [*]

Chicken eggs and other fowl eggs follow a similar trend because linoleic acid in feed is also incorporated into eggs [*].

Linoleic acid (LA) in seafood as a percentage of total fatty acids:

Wild-caught salmon: 1.35% LA [*]

Farmed salmon: 14.4% LA [*]

Oysters (wild-harvested or ocean aquaculture): 2% LA [*]

Wild-caught tilapia: 2.1-7.9% LA [*]

Farmed tilapia: 2.8-13.6% LA [*]

Wild-caught shrimp: 7.3% LA [*]

Farm-raised shrimp: 13.4% LA [*]

Note: Linoleic acid as a percentage of fatty acids, used in this section, is not equivalent to linoleic acid as a percentage of calories used in other sections of this article. Total linoleic acid in each animal product will vary according to the serving size and amount of fat per serving.

For more insight on the topic of linoleic acid in the agricultural food system, watch this in-depth presentation from Dr. Anthony Gustin:

Linoleic Acid in Restaurant Foods

The linoleic acid content in restaurant food varies from one business to another, but nearly every restaurant uses vegetable oils made from seed crops that are high in linoleic acid (LA).

Here are typical LA levels of common restaurant foods from the USDA nutritional database:

A medium-sized garden chicken Caesar salad (311 g) with two tablespoons of dressing contains 9 grams of linoleic acid [*,*].

An order of nachos with cheese (174 g) contains 7.6 grams of linoleic acid [*].

A fried chicken sandwich (140 g) contains 7.3 grams of linoleic acid [*].

A medium order (145 g) of french fries contains 7.2 grams of linoleic acid [*].

A slice of German chocolate cake (109 g) contains 5.5 grams of linoleic acid [*].

A hamburger with a four-ounce ounce beef patty (175 g) and two tablespoons of condiments contains 5.2 grams of linoleic acid [*,*].

A small chicken taco or burrito (98 g) contains 2.8 grams of linoleic acid [*].

A medium (43 g) breadstick with parmesan cheese contains 2.3 grams of linoleic acid [*].

A piece of cheese pizza (143 g) from a large pizza contains 1.7 grams of linoleic acid [*].

Another reason to reduce your intake of linoleic acid from restaurant foods is that restaurants use reheated vegetable oils that are packed with inflammatory oxidized byproducts of linoleic acid [*].

If you want to eat out but still avoid linoleic acid, you can order beef (not chicken or pork) or wild-caught seafood with vegetables and have them pan-seared or grilled without any oils.

Can You Recover from Long-term High Linoleic Acid Consumption?

Yes, you can recover from high linoleic acid by lowering your dietary intake as much as possible. Your levels will begin decreasing immediately, but studies show it can take 1-4 years for some tissues. Exercise, intermittent fasting, and consuming omega-3 fatty acids and other low-linoleic acid fats may help speed the process.

Diets high in linoleic acid cause it to accumulate in adipose (fatty) tissue, skeletal muscle, red blood cells, and most other cells [*,*,*,*]. The most crucial step you can take is to reduce your intake by eating a diet free of seed oils and avoiding the prepared and packaged foods that contain them.

The dietary requirement for linoleic acid is only 1-2% of total calories (for example, 2-4 grams of linoleic acid for an adult consuming 2,000 calories per day). And linoleic acid exists naturally in trace amounts in many healthy whole foods, so you don’t need to intentionally seek out linoleic acid to prevent deficiency [*].

Research also suggests that if you’re burning body fat and losing weight (which is also easier when you reduce your linoleic acid intake), the stored linoleic acid in your adipose tissue is sufficient to prevent deficiency, even if you eat no linoleic acid at all [*].

Once you stop eating excess linoleic acid, here’s how long it takes to lower tissue stores to healthy levels according to research:

Minutes to hours for circulating free fatty acids (FFAs) in plasma, depending on age, sex, weight, fitness, and whether you’re resting or exercising [*,*,*].

Fatty acids in most cell membranes are replaced quickly, after 1-2 cell divisions (typically 24-48 hours), and additional linoleic acid inclusion would depend on your circulating plasma levels of linoleic acid and recent consumption levels [*].

About 29 hours for intramuscular triacylglycerols (stored fatty acids in muscle tissue) [*].

Four months or less in erythrocytes (red blood cells), because they’re replaced at that rate [*].

Two to four years for adipose tissue, although it may be shorter if you exercise or lose excess body fat [*].

A study also found that reducing linoleic acid intakes (from 6.7% down to 2.4% in the research participants) resulted in significantly reduced levels of harmful linoleic acid byproducts in plasma in 12 weeks or less [*].

Because exercise increases fat-burning and turnover of fatty acids like linoleic acid, regular exercise is also a good idea to speed up the process of decreasing your linoleic acid levels [*]. Lower-intensity aerobic exercise as opposed to high-intensity methods is more effective for this purpose [*].

Another optional but effective way to speed your linoleic acid clearance is by fasting (also called intermittent fasting), or skipping some meals in a controlled and sustainable way.

Fasting for six hours or longer, not including sleep, is proven to increase lipolysis (release of stored fats) and beta-oxidation (fat-burning), which are extremely helpful for linoleic acid reduction [*,*,*,*,*,*]. Longer fasting durations of 12-36 hours are even more effective but may not be safe for some people [*].

And because you’re not consuming any fatty acids while fasting, research suggests that the linoleic acid released at this time isn’t incorporated into fatty acid storage [*].

For people who are unable to fast, restricting calories by about a third or more every other day and eating normal, maintenance calories on alternate days may have a similar effect [*].

You can also combine low-intensity exercise with fasting or calorie restriction to further increase lipolysis (release of fatty acids) and beta-oxidation (using fatty acids for fuel), which is helpful for depleting linoleic acid in tissues [*].

According to one human study, you may be able to make the practice of fasting even more effective for reducing your body’s linoleic acid levels by consuming seafood rich in omega-3 EPA and DHA shortly after ending your fast [*].

Omega-6 linoleic acid competes with omega-3 fatty acids, which is why it can lower them when consumed in excess, but consuming omega-3s in the absence of linoleic acid after a fast could have the reverse effect [*].

Eating more whole foods rich in omega-3s may help reduce linoleic acid levels even if you don’t fast, but only if you significantly reduce your LA intake [*].

Be sure to consult your doctor before exercising or fasting for the first time, and keep in mind that the single most impactful change you can make is avoiding seed oils and other foods high in linoleic acid.

*References: ↑ = Increased consumption of; Severe obesity: BMI 35–40 [*]; Heavy smoking: ≥10 cigarettes/day (avg 21.97 or ~1 pack) [*,*]; Vegetable oil: Increase consumption by 12% of calories [*]; Physical inactivity: <2 times/week [*]; Heavy drinking: >14 drinks/week for men or >7 drinks/week for women [*,*,*]; Moderate smoking: <10 cigarettes/day [*]; Sugar: ≥73.2g sugar/day for women or ≥79.7g sugar/day for men [*]; Processed meat: Increase of at least 2 servings/week [*,*,*]; Air pollution: per 10 μg/m3 long-term exposure to PM 2.5 [*,*]; Red meat: Increase of at least 2 servings/week [*,*,*]; Sodium: >2,300 mg/day [*]